I recently had the opportunity to solve an interesting optimization problem, the Airplane Overbooking Problem. I’ll aim to use this this blog to introduce the problem, the stastical analysis used to solve it and a pythonic implementation of my methodology. Hopefully, the blog also presents an interesting insight into scientific programming and how standard stastical thinking translates itself into code.

The airplane overbooking problem presents itself as an optimization problem where a typical airline company must maximize its revenue by considering the number of seats available on a standard aircraft and the number of tickets offered to potential customers. Assuming our aircraft accomodates 180 passengers (Airbus A320), we assume that on a typical day tickets are priced at $200. It is obvious to observe that in an ideal scenario, an airline company would like to offer 180 seats, and 180 passengers board the flight. This ideal scenario indicates our theoretical limit on the revenue the company can make for a given flight. However, in reality, there are a reasonable amount of no-shows, people who cancel the tickets, delays due to preceding connecting flights, and in some cases, an outright lower demand for tickets.

In such cases, offering 180 tickets may not be optimal, factoring lost revenue due to empty seats. Considering this, airlines often overbook flights, i.e. offer an additional “x” number of seats. This allows them to give those extra seats to the extra passangers who show up, thus making up for any potentially lost revenue. The trouble happens when more than 180 passengers do show up, like during peak holiday seasons, and suddenly airlines have to compensate heavily for inconvenience caused to the extra passengers who show up, including hotel, transporation and re-booking charges. Altogether, these prices may run all the way up to $700-1000. With enough number of compensations, the overall revenue begins taking a hit.

Considering all the factors laid above, this problem becomes an interesting optimization problem, where we optimize for the number of overbooked seats the airline company offers in a manner as to maximize revenue. As such, we make certain assumptions before we jump into the mathematics.

Starting of with modelling a basic structure for passengers that board the flight given the airline offering a certain number of tickets N, we can use the binomial distribution. Binomial Distribution is useful to model events which model an even similar to a coin toss, i.e. an event with a probability p of occuring, and a probability 1-p of not occuring. In this case, that p is represented by a passenger showing up to board the flight. Data shows that percentage being around 95%, hence we set our p as 0.95.

Binomial distributions are represented as,

\[P(N=n) = {180 + overbook\choose n}p^n(1-p)^{180+overbook-n}\]180 + overbook represents the total number of tickets offered by the airline company, defined as the original 180 seats and a variable overbook to account for the number of extra seats offered by the airline. N represents the number of customers who show up at the ticketing counter. Here, binomial theorem allows us to optimize for the number of overbooked seats. Given the probabilistic aspect of running this experiment once, we convert our experiment into a Monte Carlo setting to allow for more deterministic results.

We state our problem mathematically as follows: given an airline company offering 180+overbook number of tickets, with each ticket costing \$ 200 and airline’s recompensation price to each passenger bumped costing \$ 800, we aim to optimize overbook in such a manner as to earn the highest possible revenue. To do this, we must determine a revenue function $r(n)$ that we shall maximize. Considering we make money from each passenger boarding the plane and lose income from each passenger being bumped off and recompensated, we define $r(n)$ as,

$r(n) = 200n$ if $n < 180$, and,

$r(n) = 200(180) - 800(n-180)$ if $n > 180$

where $n$ is the number of passengers who show up given the airline company offering 180 + overbook tickets. The revenue we expect to make given our overbooking policy is,

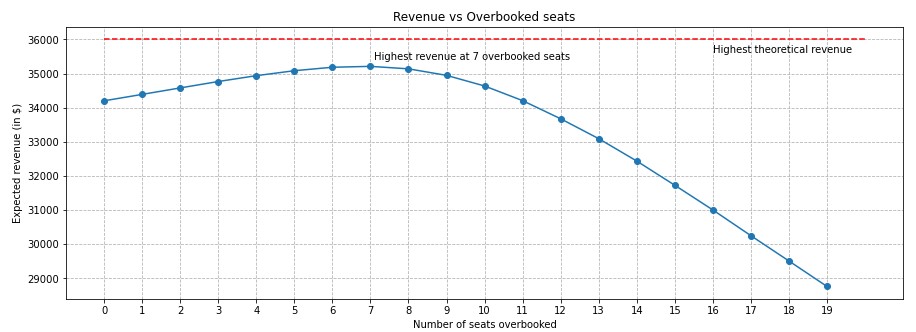

\[E(r \vert overbook) = \sum_{n=0}^{180+overbook} P(N=n \vert overbook)r(n)\]$P(N=n)$ is conditioned based on binomial distribution as above, determined by fixing a value for $overbook$. We test this algorithm in a Monte-Carlo setting by checking the expected revenue for different values of $overbook$ and plot a graph to determine the optimal $overbook$ that provides maximal revenue.

I have included the code I used to design this problem along with explanations below.

import numpy as np

# Check revenue for 180 to 180 + 20 tickets,

# where 20 is the maximum overbooked tickets the airline offers

exp_revenue = []

for n in range(180, 200):

rev_ls = []

# Running 100000 iterations for deterministic results

for i in range(100000):

# As disucssed earlier, the probability of a single passenger

# showing up, according to airline data, is around 95%. Therefore,

# we can sample the number of passengers who show up from a binomial distribution.

show = np.random.binomial(n, 0.95)

# Computing total revenue

if show <=180:

rev = 200 * show

else:

rev = 200 * 180 - 800 * (show-180)

rev_ls.append(rev)

rev_mean = np.mean(np.array(rev_ls))

exp_revenue.append(rev_mean)

A plot may be constructed to determine the optimal number of overbooked seats.

It may be observed that, despite not reaching the theoretical limit, this algorithm provides an excellent paradigm for the number of overbooked seats we can offer to come close to the theoretical limit. It is also observed that after 7 seats, there is a sharper decline in the maximum revenue earned.

It may be interesting to note that in more realistic settings, the demand for tickets is not always the same. Seasonal changes in demand are often observed, such as higher spikes closer to holiday and tourism seasons. With a simple modification to the algorithm, passenger data may be considered and seasonal changes can be factored into the algorithm using Poisson distribution.

\[P(N=n) = \frac{\lambda^{n} {\rm e}^{- \lambda}}{n!}\]Poisson distribution is used to express the probability of a given number of events occuring in a fixed interval of time or space. In the context of this algorithm, Poisson distribution can be used to model customer demand for tickets. Using appropriate data, we can extrapolate how many total customers will require tickets, and factor it into the total number of tickets offered by the airline company.

We do this by sampling the total customer from a poisson distribution, and use that number to generate a binomial distribution around how many customers will show up. It follows that should the demand be greater than the number of seats being offered by the airline, we limit the demand to the number of seats offered. The $\lambda$ parameter required for computing the poisson distribution is typically obtained from the data. For this example however, I’ll set $\lambda = 187.5$ going by the fact that in the previous experimentation, optimal overbooked seats is 7. I have included a code to include this experiment below,

import numpy as np

# Check revenue for 180 to 180 + 20 tickets,

# where 20 is the maximum overbooked tickets the airline offers

exp_revenue = []

for n in range(180, 200):

rev_ls = []

# Running 100000 iterations for deterministic results

for i in range(100000):

# Calculate the total demand by sampling it from a poisson distribution

# If the demand is greater than the total number of tickets offered,

# set demand equal to the number of tickets offered.

# Else, use new demand to model the binomial sampling.

demand = np.random.poisson(187.5)

if demand >= n:

demand = n

show = np.random.binomial(demand, 0.95)

# Computing total revenue

if show <=180:

rev = 200 * show

else:

rev = 200 * 180 - 800 * (show-180)

rev_ls.append(rev)

rev_mean = np.mean(np.array(rev_ls))

exp_revenue.append(rev_mean)

And a corresponding plot for observing revenue vs. overbooked seats is,

It may be observed that by factoring in demand, a lower optimal revenue is observed. This typically matches common sense, since high demands are rare as opposed to day to day operations.

Credits to Cory Simon’s blog for a theoretical foundation of the topic.